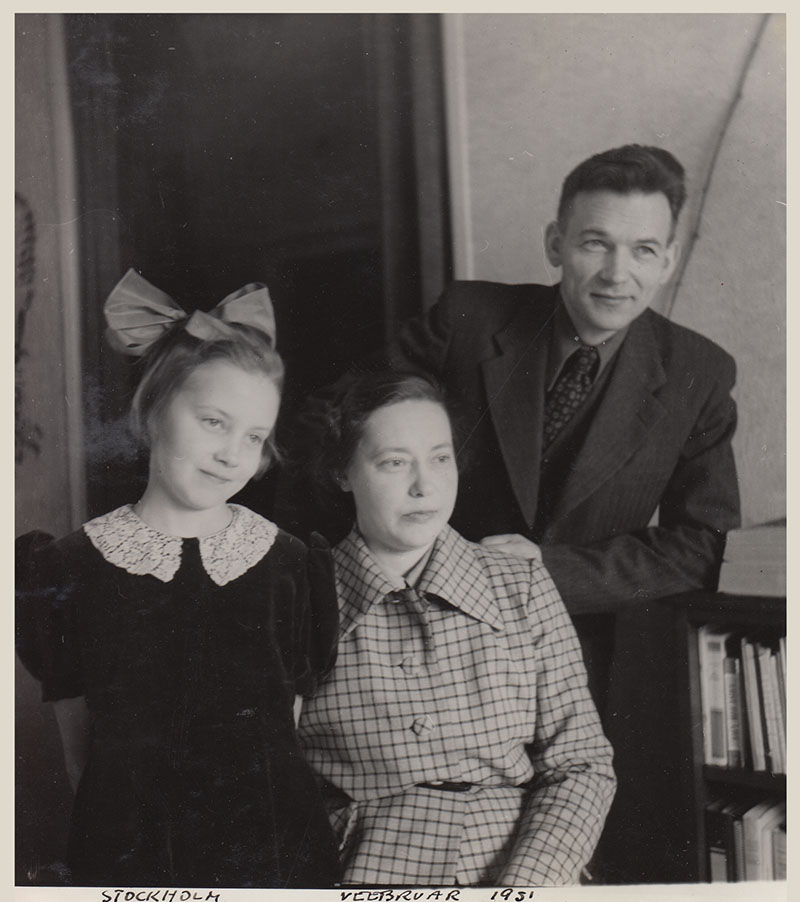

We had lived six years in Sweden after escaping from Estonia during World War II. While in Sweden, thanks to the fact my parents both spoke English fairly fluently, we had completed all requirements for immigration to Canada. In early March 1951 we made our way by regular passenger trains from Stockholm, Sweden to Bremerhaven on the German coast. There we stayed for a few weeks in an army barracks then functioning as a temporary holding camp operated by the International Refugee Organization, until we were assigned to a ship. Aside from beds and meals, occasional entertainment was provided for this huge temporary community. It was around Easter time, therefore we were shown a film depicting Christ carrying his Cross. As an 8 year old, I was strongly impressed. The only film I had ever seen previously was Disney’s Cinderella, in Swedish.

We were permitted to leave the barracks to visit the town. Upon our return each time, our documents were thoroughly inspected by men in uniform. Someone sprayed a puff of DDT down the back of our necks to ward off lice. Only then could we proceed to our quarters. Everyone was disgusted and immediately washed off as much of the powder as possible. I had not heard this word “lice” before, and asked mom whether a louse is about the size of a cow.

Finally, onboard our ship, we saw that our fellow passengers came from all over Europe. Announcements over the PA system took a long time because they had to be made in many languages; not in Estonian though. Not enough Estonians on board to warrant that. My parents were in high demand among the other Estonians aboard to translate all announcements.

Once again, we were all provided accommodation and meals by IRO. Some people, particularly those from south and east Europe, had obviously suffered hunger in recent years as well as during World War II, causing them to force feed their young children until the kids became ill in the ship’s hallways. Bear in mind, this was only six years after the end of the War.

Everyone was provided cafeteria meals on a metal tray with depressions for the different foods i.e. mashed potatoes, veggies, meat, bread, dessert. We were aboard a troop carrier, not a cruise line. One day I announced there was rice in my milk. After a panicky inspection of the contents of my glass, my parents talked about powder, water and tiny ice pellets. I was puzzled. They should have known that milk comes from cows???

Accommodations aboard were separate; men in one area of the ship and women with children in another. The nationalities were all mixed together within each area. We slept on hanging bunks, four vertically, one above of the other. Approximately 16 people per room if I recall right. The beds swayed even more than the ship itself in rough Atlantic Ocean waves. My mom kept a blue bag beside her on the bunk below mine. Before leaving Sweden, she had bought some kind of blue rubbery waterproof material (in 1951 the plastics industry was just getting started, no suitable plastic bags available yet) and sewed three bags which she kept handy throughout the ocean crossing.

Am guessing the trip across the Atlantic was free of charge for all aboard these IRO ships. As wards of the IRO, we were required to make a contribution by volunteering to work aboard this troop carrier. Women swabbed hallway floors and walls. My mom tried her best while carrying her blue bag with her. Men scraped rust off the decks. Kids just hung around.

For our family, the final stage of immigration proceeded smoothly on Halifax’s Pier 21. Then we were suddenly on our own, here, in hazy Canada!

First, we had to find a place to stay. I vaguely recall a strange-looking tall skinny wooden house, very different from those in Sweden. We stayed in a room there for two nights, giving my parents a chance to exchange currency and buy three CNR railway tickets to Vancouver, BC.

That cross-country trip took five days and four nights.

Oddly, I do not remember much of the scenery but I do remember a fellow train passenger – a six year old Canadian girl who had painted finger nails. I was not allowed to wear nail polish and this girl was two years younger than me, yet she had a shiny red coating on her nails! No fair!

We could not afford to eat in the dining car, so, whenever the train had a longer stop, my father would run off, look for a nearby grocery store and come back with bread, butter, cheese, sausage, milk, jam, apples and paper plates. I was always afraid he would not make it back to the train on time. But he never missed. He mangled the soft spongy white bread with his pocket knife, unaware that such a thing as sliced bread existed and was available in this new home country of ours. The train was not full, so we were able to stretch out to sleep on the wide upholstered seats with our sweaters for pillows and coats as blankets, much like most of the other long distance passengers.

On April 12th, we arrived at the Canadian National Railway station on Main Street in Vancouver. All three of us walked out of the station into salt air and cheerful warm bright sunlight albeit in a somewhat dodgy neighbourhood. Still, for the first time, I clearly felt I had arrived in Canada. It immediately felt like home and I felt comfortable about that thought.

With all the might of a skinny 8-year old who could not speak the local language, I was ready to take on whatever challenges lay ahead.

– Helgi Leesment

Note: The cities which were major departure and arrival points on either side of the Atlantic have turned their former emigrant/immigrant processing facilities into museums.

The German Emigration Center is dedicated to the history of those who left Bremerhaven by sea for North American destinations.

The Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, is Canada’s national museum of immigration by sea. The museum occupies Pier 21, which had functioned as an ocean liner terminal and immigration shed from 1928 to 1971.